by Nils Muižnieks, Europe Director, Amnesty International

This opinion piece was originally published in the EU Observer

At its London headquarters, Amnesty International has a large sign emblazoned in a hallway encouraging you to “Take Injustice Personally”. For activists, this means not becoming hardened or cynical, but allowing the suffering of others to touch us personally. It is this personal sense of injustice that should motivate us to speak out on behalf of people whose human rights are violated the world over.

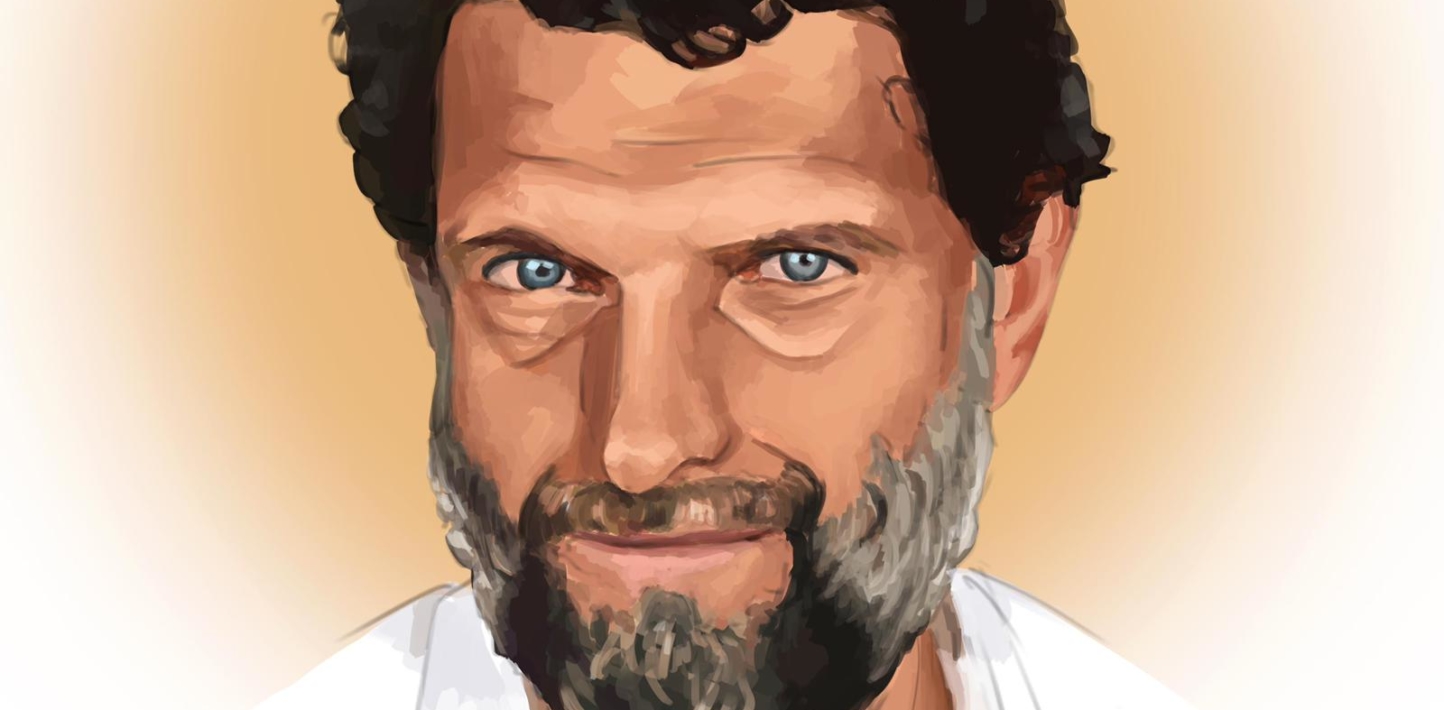

In Europe, there is a prominent victim of injustice whose case I take personally. It seems that Turkey’s leaders do as well, and to prove it, they have gone to absurd lengths to keep him behind bars. That victim is philanthropist Osman Kavala, one of Turkey’s best-known human rights defenders, who has been unjustly imprisoned for more than four years.

I regularly met with Osman Kavala not only in my previous office in Strasbourg, the seat of the Council of Europe, of which Turkey is a member state, but also during regular visits to Turkey. As a prominent figure in Turkey’s beleaguered civil society, and with his vast knowledge of its diversity and history, it was always enlightening to speak with him.

While Osman Kavala’s analysis and understanding of Turkey were of great value for representatives of international bodies, it is for his support to the fields of arts and culture that he is most well-known and appreciated for – Osman Kavala is also a founder of the Turkish School of Political Studies, a member of an association of 21 democracy academies affiliated with the Council of Europe. I happen to be this association’s president.

I am often asked: why Osman Kavala? Why has he been singled out with one baseless accusation after another?

It is for the Turkish authorities alone to answer this question. But the facts are self-evident, and as the Strasbourg Court noted, there is a determination to punish and silence him for his human rights work. This sends a stark warning to the larger Turkish society: no matter how legitimate or lawful your work, you can be imprisoned for years without a guilty verdict.

Since November 2017, Osman Kavala has faced one fantastical accusation after another. Firstly, it was organizing and financing the Gezi Park protests – mass protests in spring 2013 against an urban development project. When a court acquitted him of that charge in 2020, he was immediately rearrested for allegedly being behind the 2016 failed coup attempt, a charge that was soon replaced by ‘military and political espionage’. Over last summer, in a sequence of events that would be unbelievable in a work of fiction, the three charges he faced were joined in one prosecution with 51 others. These include 35 football fans whose 2015 acquittal for ‘attempting to overthrow the government’ during the Gezi protests, was overturned by the Court of Cassation in April this year, some six years later. In August, this long forgotten, unrelated case was joined with the two existing prosecutions of Osman Kavala – Gezi re-trial following his acquittal was overturned on appeal and ‘espionage’ case – in a new mass trial, barely disguising the authorities’ attempt to prolong his unjust imprisonment.

The form of “justice” encapsulated in Osman Kavala’s prosecution is reminiscent of the famous line: ‘show me the man, I will find the crime’. Indeed, Turkey’s leaders have found their man and keep trying to find a crime to pin on him. This is a country where thousands of judges and prosecutors have been summarily dismissed and detained on vague accusations under anti-terrorism laws. Only last week, the European Court of Human Rights found Turkey had violated the liberty and security of 427 judges and prosecutors when they were detained in the aftermath of the 2016 coup attempt.

It is not only me who finds the charges against him absurd. The European Court of Human Rights, whose rulings Turkey has accepted as binding, delivered a judgment in 2019 calling for Osman Kavala’s immediate release, as it found his detention to pursue an ‘ulterior purpose’ – to silence him. Since then, the Committee of Ministers – the body composed of foreign affairs ministers’ deputies of 47 member states charged with executing judgments – has called seven times for Osman Kavala’s release.

This week as they meet again, these same member states can show they mean business by ratcheting up the pressure on Turkey. Stubbornly refusing, as Turkey has done, to honour its obligations and implement a judgment of the European Court of Human Rights, they could – and should – initiate ‘infringement proceedings’. That is resending the judgment back to the European Court to condemn Turkey’s refusal to comply with the binding judgment. This has only been done once before in the history of the Court, in the case of Ilgar Mammadov vs. Azerbaijan ultimately leading to Ilgar Mammadov’s release.

Four years behind bars in the absence of a criminal conviction, facing farcical charges without any evidential basis, Osman Kavala’s release is long overdue. Representatives of the other 46 Council of Europe member states should nudge Turkey to do the right thing by insisting that human rights are a common responsibility, and that Turkey cannot disregard the rules any longer. The friends of human rights must vote for infringement proceedings, as abstaining in the vote this week effectively means voting in favour of letting Turkey abscond from its responsibilities.

Let us watch where the conscience of Europe stands. Will they take Osman Kavala’s rights personally?

Nils Muižnieks, Amnesty International’s Europe Director, former Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights