Iranian and Turkish security forces have repeatedly pushed back Afghans who attempt to cross their borders to reach safety, including by unlawfully opening fire on men, women and children, Amnesty International said today. In a new report, They don’t treat us like humans, the organization also documents numerous instances – mostly at the Iranian border – where security forces have shot directly at people as they climbed over walls or crawled under fences. Afghans who do manage to enter Iran or Turkey are routinely arbitrarily detained, and subjected to torture and other ill-treatment before being unlawfully and forcibly returned.

Amnesty International researchers visited Afghanistan in March 2022, and conducted interviews in Herat City and Islam Qala border town. They interviewed 74 Afghans who had been pushed back from Iran and Turkey, 48 of whom reported coming under fire as they attempted to cross the borders. None of the people Amnesty International spoke to had been able to register an asylum claim in either country, and the majority were returned to Afghanistan in violation of international law.

One year after the end of airlift evacuations from Afghanistan, many of those left behind are risking their lives to leave the country

Marie Forestier, Researcher on Refugee and Migrants Rights

“One year after the end of airlift evacuations from Afghanistan, many of those left behind are risking their lives to leave the country – Afghans who have travelled to the Iranian and Turkish borders over the past year, in search of safety, have instead been forcibly returned under fire. We documented how Iranian security forces have unlawfully killed and injured dozens of Afghans since last August, including by firing repeatedly into packed cars. Turkish border guards have also unlawfully used live ammunition against Afghans, firing into the air to repel people, and also shooting at them in some cases,” said Marie Forestier, Researcher on Refugee and Migrants Rights at Amnesty International.

“The dangers don’t end at the borders. Many Afghans we spoke to had spent time in arbitrary detention, either in Turkey or in Iran, where they were subjected to torture and other ill-treatment before being unlawfully returned. We are calling on Turkish and Iranian authorities to immediately end all pushbacks and deportations of Afghans, end torture and other ill-treatment, and ensure safe passage and access to asylum procedures for all Afghans seeking protection. Security forces must immediately end the unlawful use of firearms against Afghans at the borders, and perpetrators of human rights violations, including unlawful killing and torture, must be held accountable.”

Amnesty International also calls on the international community to provide financial and material support to countries which host large numbers of Afghans, including Iran and Turkey. They must ensure that this funding does not contribute to human rights violations – this is critical, as the European Union has already provided funds for Turkey’s new border wall, as well as for the construction of several ‘removal centres’ where Amnesty International documented Afghans being detained. Other countries must also increase resettlement opportunities for Afghans who need international protection.

A long and risky journey

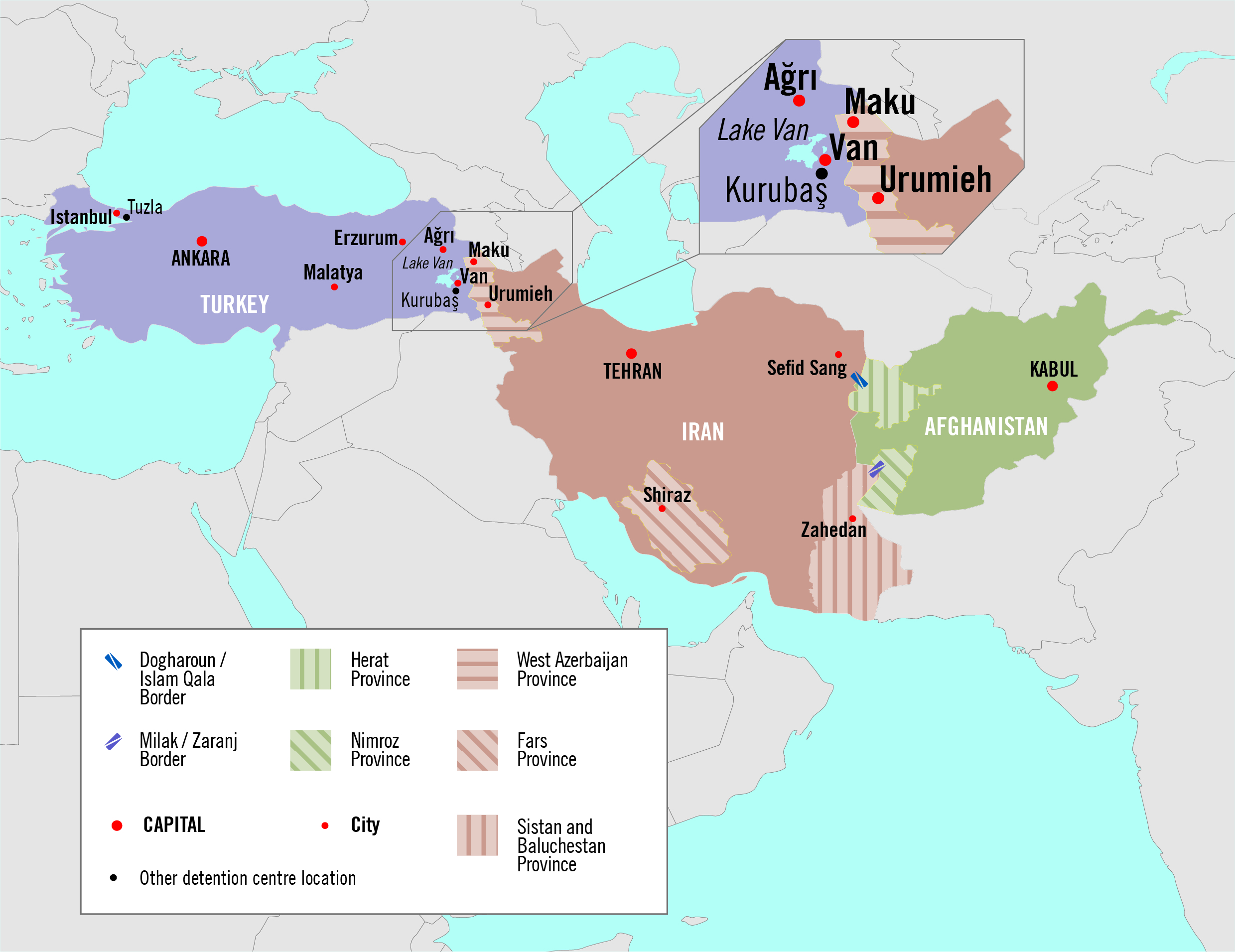

Hundreds of thousands of Afghans have fled their country since the Taliban took power in August 2021. Afghanistan’s neighbouring countries have closed their borders to Afghans without travel documents, leaving many people with no choice but to travel irregularly. This means entering Iran through informal border crossings – such as through crawling under a fence near an official crossing in Afghanistan’s Herat Province, or climbing over a two-metre-high wall in Nimroz province.

My nephew arrived at the wall of the border, climbed it and he raised his head up over the top. [Iranian forces] shot him in the head

Ghulam*

Those who are not immediately detained by Iranian border guards then travel on to various cities in Iran, or to the Turkish border nearly 2000 km away in north-western Iran. At both the Afghan-Iranian and Turkish-Iranian borders, Afghans are subjected to violent and unlawful pushbacks – from Iran back into Afghanistan, or from Turkey into Iran.

Amnesty International researchers travelled to Afghanistan and Turkey in March and May 2022. They interviewed doctors, NGO workers and Afghan officials, as well as 74 Afghans who had attempted to cross into Turkey or Iran. Some people had made multiple attempts, and some had travelled in groups; based on their accounts, Amnesty International documented a total of 255 instances of unlawful return between March 2021 and May 2022.

Killed trying to enter Iran

Amnesty International interviewed the relatives of six men and a 16-year-old boy who were killed by Iranian security forces as they attempted to cross into Iran between April 2021 and January 2022. In total, the organization documented 11 killings by Iranian security forces, though the true death toll is likely to be significantly higher. The lack of comprehensive reporting procedures means there are few publicly available statistics, but humanitarian workers and Afghan doctors told the organization they recorded at least 59 deaths and 31 injuries between August and December 2021 alone.

I saw that my son was dead. I was next to his body in a taxi

Sakeena*

Ghulam* described how his 19-year-old nephew was shot and killed in August 2021:

“He arrived at the wall of the border, climbed it and he raised his head up over the top. They shot him in the head, in the left temple. He fell to the ground on the [Afghan] side of the border.”

Some of the documented shootings took place inside Iranian territory. Sakeena, 35, told Amnesty International how her 16-year-old son was shot dead as they walked away from the Iranian border:

“I heard my son screaming for me. He had been hit by two bullets in his ribs. I don’t know what happened after I fainted […] When I gained consciousness, I was in Afghanistan. I saw that my son was dead. I was next to his body in a taxi.”

Shootings by Turkish security forces

Amnesty International interviewed 35 people who had attempted to cross into Turkey, 23 of whom reported coming under fire. Researchers interviewed one Afghan man who said he had witnessed the killings of three teenage boys by Turkish security forces. Other witnesses described the injury of six men and three boys by Turkish security forces, and Amnesty International interviewed two men who had sustained gunshot wounds at the Turkish border.

A two-year-old child was shot in the kidney, and a six-year-old child was shot on his hand. I was very scared

Aref*

Aref, a former Afghan intelligence officer who fled after receiving death threats from the Taliban, said he witnessed young children being injured by Turkish security forces:

“They shot directly at us, not in the air (…) I witnessed a woman and two children who were injured. A two-year-old child was shot in the kidney, and a six-year-old child was shot on his hand. I was very scared.”

None of those killed or injured appear to have represented any imminent threat to security forces or others – let alone a threat of death or serious injury -meaning the use of firearms would have been unlawful and arbitrary.

In some cases, Iranian security forces appear to have used firearms in a manner that demonstrated an intention to kill, for example by shooting directly at individuals from close range.

“Any killings resulting from deliberate and unlawful use of firearms by agents of the state must be investigated as potential extrajudicial executions,” said Marie Forestier.

A crisis of systemic impunity for widespread patterns of torture, extrajudicial executions and other unlawful killings prevails in Iran. Amnesty International therefore reiterates its call on the UN Human Rights Council to establish an independent investigative and accountability mechanism to collect and analyze evidence of the most serious crimes under international law committed in Iran, including against Afghans in the context of pushbacks, to enable future prosecutions.

Detained and tortured

Almost all interviewees who were intercepted once inside Iran or Turkey, and not immediately pushed back, were arbitrarily detained. Detention time ranged from one or two days to two-and-a-half months. Twenty-three people described treatment that would amount to torture or other ill-treatment while in detention in Iran, as did 21 people detained in Turkey.

The policeman sat on my friend, as if he was sitting on a chair. He sat there and lit a cigarette

Hamid*

Hamid described how Turkish security forces beat him and his friend in detention:

“One of the policemen beat my friend with the butt of his gun, and then the policeman sat on my friend, as if he was sitting on a chair. He sat there and lit a cigarette. Then he hit me on my legs with his gun as well.”

Several people Amnesty International interviewed were detained in Iran after sustaining gunshot wounds.

Amir was injured when a bullet fired by Turkish security forces grazed his head. After being pushed back to Iran, Amir was detained by Iranian security forces who beat him on his head:

“They would beat me directly on the wound, and it would start bleeding again… One time I said, ‘please don’t beat me on my head,’ and the guard [at the detention facility] said, ‘Where?’ When I showed him, then he beat me in that same spot,” Amir said.

If the EU continues funding detention centres where Afghans are held before being unlawfully returned, it risks being complicit in these violations

Marie Forestier

Eleven Afghans unlawfully returned by Turkish authorities had been detained in one of the six removal centres in Turkey whose construction the EU has partially funded.

“The European Commission must ensure that migration and asylum related funding to Turkey does not contribute to human rights violations. If the EU continues funding detention centres where Afghans are held before being unlawfully returned, it risks being complicit in these appalling violations,” said Marie Forestier.

Denied international protection

None of the Afghans interviewed by Amnesty International was able to register a claim for international protection, either in Iran or in Turkey. Interviewees said they attempted to tell authorities they would be at serious risk of human rights violations if returned to Afghanistan, but their fears were dismissed.

Iranian security forces transferred detainees by bus to the Afghan border, while Turkish security forces usually transferred them back to Iran at irregular crossings. Ten of those deported from Turkey were sent straight back to Afghanistan by plane. Turkey resumed charter flights to Afghanistan in late January 2022. At the end of April, the Turkish migration authority announced on its websites that charter flights had already returned 6805 Afghan citizens.

They beat me, pushed me to the wall. Two men held my legs and one was sitting on my chest. Two others [made me sign] the paper

An Afghan man who was returned from Turkey

All interviewees who had been returned said that Turkish and Iranian authorities coerced them to leave. Amnesty International heard how detainees sobbed and fainted when they heard they were being returned to Afghanistan, and how a man attempted to take his own life by jumping out of a window.

Eight people detained and then deported on charter flights from Turkey said Turkish authorities pressured them to sign documents stating they were leaving voluntarily. One man said:

“I told [security forces] that I was at risk in Afghanistan. They didn’t care. They beat me, pushed me to the wall. I fell down on the ground. Two men held my legs and one was sitting on my chest. Two others put my fingers on the paper.”

This is consistent with previous Amnesty international research on “voluntary” returns from Turkey.

“The international legal principle of non-refoulement prohibits states from returning anyone to a territory where they are at risk of persecution and other serious human rights violations. We urge the Turkish and Iranian authorities to abide by this obligation and stop forcing people back to danger in Afghanistan,” said Marie Forestier.

“The international community must also arrange safe passage and evacuations for Afghans who are at risk, and step up with a coordinated response to share the responsibility of hosting Afghan refugees.”

*All names are pseudonyms