- By Camila Rodríguez

- It was first published by EU Observer here

I am writing these words in exile. I left Cuba almost exactly a year ago, after months of being threatened by State Security to stop my work defending human rights inside Cuba. My story is the story of dozens of activists, journalists, political dissidents and non-conformist artists who in the last few years have been forced to board a plane. And in many cases, to also follow the migrant routes that cross half of the American continent to reach a safe place to start over.

In November, Eamon Gilmore, the European Union (EU) Special Representative for Human Rights, will arrive in a country in turmoil, as people flee government repression. He will arrive in the midst of an intensified government siege. A willingness to speak with him could lead to, at the very least, hours of interrogation or enforced disappearance for those who wish to share in first person how the Havana regime has oppressed them.

Gilmore‘s visit risks legitimizing the Cuban regime if he does not take a firm public stance on the human rights situation and voice his solidarity with human rights defenders. A regime that has systematically destroyed the possibility for independent civil society to act, has fragmented a generation of honourable people, has shattered the peace of hundreds of homes, and has worn down, if it was even possible to do so further, the hope for democracy and justice in Cuba.

If my brothers and sisters in this fight who are currently in Cuba cannot speak with Mr. Gilmore, if those who attend a meeting in a frigid room surveilled by a photo of a beautiful Cuban beach share a doctored version of our reality, I want to use this space to share five truths that the special representative should know. A reality that he should be aware of before arriving in Cuba and posing with the dictator in an image of smiles and complicity.

Firstly, this visit will take place in the context of a growing systemic crisis. Although the government does not publish updated data on poverty in Cuba, experts have warned of the increasing precarity of life for most citizens. It has prioritized the construction of hotels for foreign tourism, which is not meeting projected income levels, while public health, education and energy management all lack infrastructure. At the same time, levels of violence, femicides and anti-government public protests are on the rise.

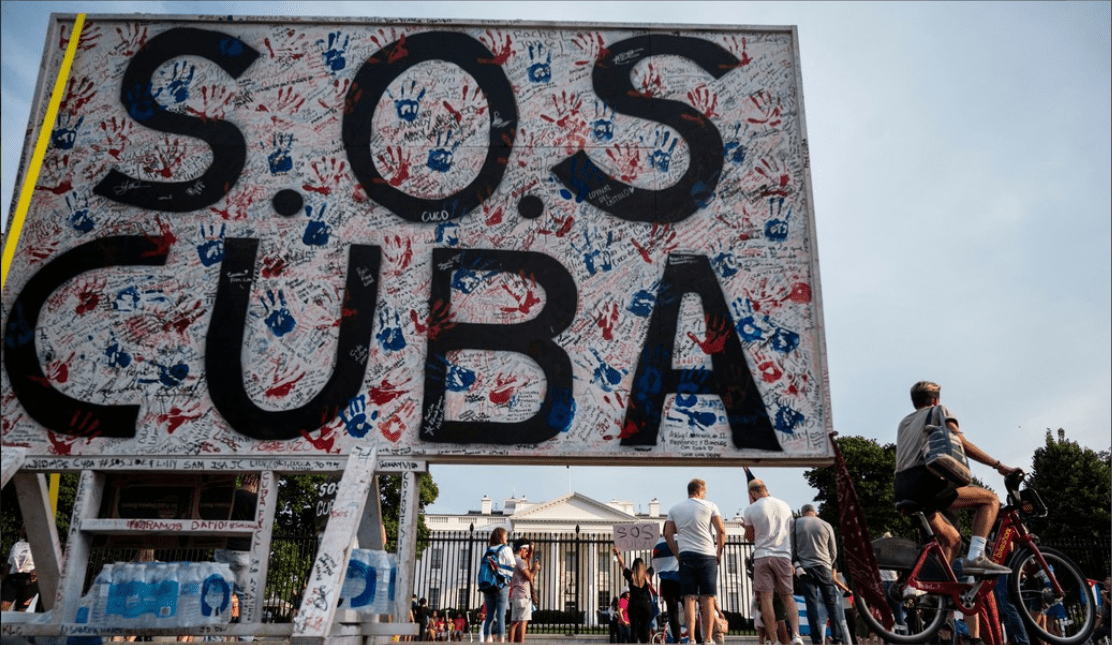

Secondly, Since the July 2021 protests, nearly one thousand people have been detained on the island for political reasons. Most of them from waves of public protests demanding decent living conditions and political freedoms. The current number of political prisoners in Cuba is several times higher than the total number in the rest of the region, even accounting for Nicaragua and Venezuela, which have been singled out for not respecting the right to free expression and association.

Thirdly detained individuals live in dire conditions, in state custody, not only exposed to illnesses such as tuberculosis, but also to torture and inhumane and degrading treatment. The constant human rights violations inside the country’s prisons occur without impartial international actors such as the EU holding in loco visits as part of oversight mechanisms, since Cuban legislation neglects or forbids them.

Fourthly, repression has intensified following the entry into force of the new Penal Code. Since last December, at least 25 Cuban dissidents have been detained, either on conviction or under investigation, for allegedly committing political crimes. The new Code, which expands the death penalty to around 20 crimes, most of them political in nature, penalizes the receipt of funds to support civil society with up to 10 years of imprisonment. Meanwhile, no provisions legalizing the rights to peaceful assembly and association have been announced.

And finally, the current political emergency in Cuba is also evident from the recent surge in people leaving the country, with numbers now totalling over 300,000 Cubans. Those who have left the country include thousands who participated in civic movements and are fleeing the country under threat from State Security. The forced expatriations of Cubans have therefore shaken a considerable portion of the Cuban population; they are not merely a repressive practice used only against activists, journalists, human rights defenders, and other key actors in society.

At a time when the EU is reviewing its foreign policy agendas and priorities for Latin America, those of us who make up independent Cuban civil society, wherever we may currently find ourselves, hope that the EU, in the agenda and goals of the Political Dialogue and Cooperation Agreement with Cuba, will implement concrete actions in support of people in Cuba and assistance for the victims of repression and their families.

If the Cuban state does not provide guarantees of respect for human rights and the existence of an independent civil society, and evaluation mechanisms, we ask that the EU suspend the inter-governmental agreement. The human rights situation has worsened in the years since its creation, we can no longer believe in the effectiveness of this agreement as an instrument in favour of human rights.

We will keep fighting, swimming against the tide perhaps, even when increased state repression forces us to do so outside of our national borders.